Xcode - xcworkspace and xcodeproj - part 2

This is an update of the previous post Xcode - xcworkspace and xcodeproj. I imagine that when I’m done, I’ll have a mini-book.

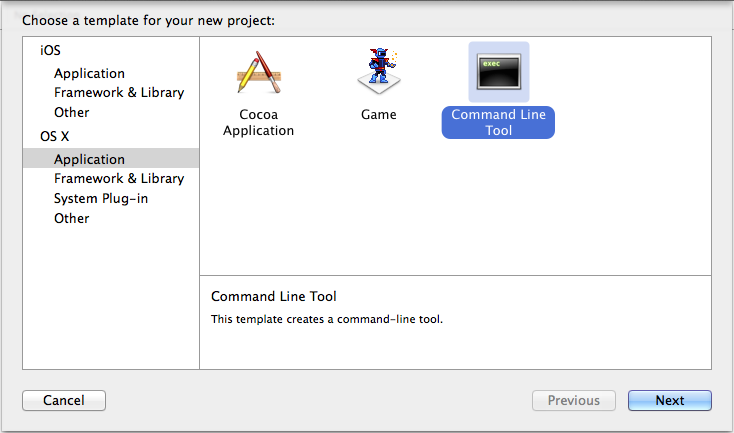

In the examples below, I used Xcode 6.1.1 to create a command-line tool:

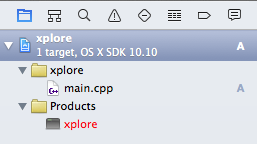

I used all defaults, and a project name of xplore. I refer to this in places as “using the Xcode wizard”.

Project with embedded workspace

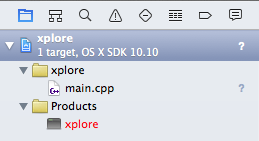

If you create a project from Xcode instead of a workspace (File -> New -> Project), you still get a workspace, it’s just embedded inside your project file. Here’s the project visually:

On disk, the project looks like this (ignoring irrelevant files):

xplore.xcodeproj/

├── project.pbxproj

└── project.xcworkspace

└── contents.xcworkspacedatacontents.xcworkspacedata looks like this:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<Workspace

version = "1.0">

<FileRef

location = "self:xplore.xcodeproj">

</FileRef>

</Workspace>Note that the project location is self:xplore.xcodeproj. I’m guessing that self in this context

means the directory containing the opened project file. In this case, we’re literally

pointing to ourself, but this keeps things sane for Xcode, I imagine.

This was the default until Xcode 4 - the workspace file existed, but was hidden from sight. With Xcode 4, the workspace file became a user-visible item so that groups of projects could be more easily navigated and built.

Project with external workspace

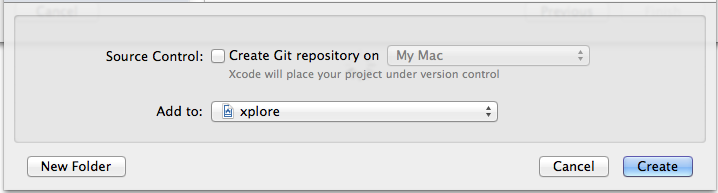

If you create a workspace (File -> New -> Workspace), then you have a separate external workspace file. Unlike like with, say, Visual Studio, you aren’t prompted to create a project. But when you now go to create a project, you’ll have a prompt to add it to a currently open workspace:

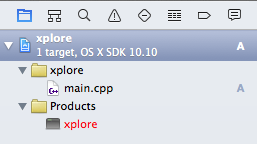

Visually, there’s little to distinguish workspace+project from workspace-inside-project:

I don’t know why the embedded workspace has ‘?’ marks next to items, and the separate workspace has ‘A’ characters.

On disk, we now have a named workspace visible in the Finder:

xplore.xcworkspace/

└── contents.xcworkspacedatacontents.xcworkspacedata looks like this:

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<Workspace

version = "1.0">

<FileRef

location = "group:xplore.xcodeproj">

</FileRef>

</Workspace>Note that the location is now group:xplore.xcodeproj. This time, our base is the directory containing

the opened workspace file.

Project file walkthrough

The project file xplore.xcodeproj is identical, whether it is attached to an external

workspace or hosting its own embedded workspace. Let’s walk through it a bit.

This is the on-disk layout, ignoring non-important files:

xplore.xcodeproj

└── project.pbxprojThe project file itself is the project.pbxproj file inside the xplore.xcodeproj package.

This is the top-level view of a project file, ignoring the contents of the objects key:

// !$*UTF8*$!

{

archiveVersion = 1;

classes = {

};

objectVersion = 46;

objects = {

...

};

rootObject = 999A68361CC86ECD0001FC48 /* Project object */;

}This is using the text version of NeXt/Mac OS X plist files; this format is now obsolete except for Xcode, and I think Xcode 7 is now switching to XML, which is a pity, because the text version is straightforward to read. Plist files have numbers, strings, uuids (which are really just strings of hexadecimal characters), lists and dictionaries.

archiveVersion is always 1, and classes is always (?) empty.

objectVersion indicates the project format. As you can see, this project was made with Xcode 3.2

compatibility:

- 39: something really old, when the project files were called .xcode

- 42: Xcode 2.4

- 44: Xcode 3.0

- 45: Xcode 3.1 compatible

- 46: Xcode 3.2 compatible

- 47: Xcode 6.3 compatible

objects is a dictionary containing all the objects in the project, as key = value, where value

can be one of the aforementioned number, string, uuid, list or dictionary. The keys in our dictionary

are always uuids. There doesn’t appear to be any rule as to the length of the uuids, I’ve seen both

24-character (12-byte) and 48-character (24-byte) uuids in Xcode projects. I’ve even see 47-character

uuids work (a bug in many versions of Mac Premake up through at least 5.0.0-alpha8). Xcode seems to

be forgiving, as long as the uuids don’t collide.

rootObject points to a PBXProject object that is the root for this project. There’s only one

PBXProject object in our project file, and this is typical.

/* Begin PBXProject section */

999A68361CC86ECD0001FC48 /* Project object */ = {

isa = PBXProject;

attributes = {

LastUpgradeCheck = 0610;

ORGANIZATIONNAME = "Blizzard Entertainment";

TargetAttributes = {

999A683D1CC86ECD0001FC48 = {

CreatedOnToolsVersion = 6.1.1;

};

};

};

buildConfigurationList = 999A68391CC86ECD0001FC48 /* Build configuration list for PBXProject "xplore" */;

compatibilityVersion = "Xcode 3.2";

developmentRegion = English;

hasScannedForEncodings = 0;

knownRegions = (

en,

);

mainGroup = 999A68351CC86ECD0001FC48;

productRefGroup = 999A683F1CC86ECD0001FC48 /* Products */;

projectDirPath = "";

projectRoot = "";

targets = (

999A683D1CC86ECD0001FC48 /* xplore */,

);

};

/* End PBXProject section */mainGroup is the PBXGroup that is the root of the displayed items. Don’t confuse this with build

instructions; this is purely for visual looks.

/* Begin PBXGroup section */

999A68351CC86ECD0001FC48 = {

isa = PBXGroup;

children = (

999A68401CC86ECD0001FC48 /* xplore */,

999A683F1CC86ECD0001FC48 /* Products */,

);

sourceTree = "<group>";

};

...Groups can contain files and more groups. The main group contains two more groups:

...

999A683F1CC86ECD0001FC48 /* Products */ = {

isa = PBXGroup;

children = (

999A683E1CC86ECD0001FC48 /* xplore */,

);

name = Products;

sourceTree = "<group>";

};

999A68401CC86ECD0001FC48 /* xplore */ = {

isa = PBXGroup;

children = (

999A68411CC86ECD0001FC48 /* main.cpp */,

);

path = xplore;

sourceTree = "<group>";

};

/* End PBXGroup section */Each of these groups contain files - or rather, PBXFileReference objects, which actually hold the

information about files:

/* Begin PBXFileReference section */

999A683E1CC86ECD0001FC48 /* xplore */ = {

isa = PBXFileReference;

explicitFileType = "compiled.mach-o.executable";

includeInIndex = 0;

path = xplore;

sourceTree = BUILT_PRODUCTS_DIR;

};

999A68411CC86ECD0001FC48 /* main.cpp */ = {

isa = PBXFileReference;

lastKnownFileType = sourcecode.cpp.cpp;

path = main.cpp;

sourceTree = "<group>";

};

/* End PBXFileReference section */For some reason, this is the one dictionary that Xcode puts into a single-line flattened form,

so for readability, I’ve shown the PBXFileReference items in indented form, instead of what’s in the

Xcode project file. All other items are displayed exactly as they are in the project file.

Since Xcode likes to put helpful comments in the project file, we can see that this matches the GUI display:

If you were to rearrange the order of the items in mainGroup, then the GUI output would change.

Going back to the PBXProject object, note that there is one other group that gets top billing, Products:

productRefGroup = 999A683F1CC86ECD0001FC48 /* Products */;In Xcode parlance, products are the things that are built. Products are built by targets, and configurations are orthogonal groups of build settings that can be applied to any number of targets or projects.

I assume that Products gets top billing in the PBXProject object so that the various actions in

Xcode know what to operate on.

The two build-related items in the PBXProject are buildConfigurationList, which points to the

project configurations available, and targets, which is the list of build targets themselves.

In this simple project, we have one build target

/* Begin PBXProject section */

999A68361CC86ECD0001FC48 /* Project object */ = {

...

targets = (

999A683D1CC86ECD0001FC48 /* xplore */,

);

};

/* End PBXProject section */This points to a PBXNativeTarget object, which describes how to build a native Mac OS X binary:

/* Begin PBXNativeTarget section */

999A683D1CC86ECD0001FC48 /* xplore */ = {

isa = PBXNativeTarget;

buildConfigurationList = 999A68451CC86ECD0001FC48 /* Build configuration list for PBXNativeTarget "xplore" */;

buildPhases = (

999A683A1CC86ECD0001FC48 /* Sources */,

999A683B1CC86ECD0001FC48 /* Frameworks */,

999A683C1CC86ECD0001FC48 /* CopyFiles */,

);

buildRules = (

);

dependencies = (

);

name = xplore;

productName = xplore;

productReference = 999A683E1CC86ECD0001FC48 /* xplore */;

productType = "com.apple.product-type.tool";

};

/* End PBXNativeTarget section */Once again, we have a reference productReference to the Products group, presumably because that’s

how Xcode finds where to put the built target.

The actual binary type is noted by the productType key: its value declares this to be a command-line

tool, e.g. com.apple.product-type.tool.

Note that the target also has a buildConfigurationList. In this case, this points to configurations

for the target, which are distinct from configurations for the project. So let’s look at configurations

for a bit.

The project configurations are in a XCConfigurationList:

/* Begin XCConfigurationList section */

999A68391CC86ECD0001FC48 /* Build configuration list for PBXProject "xplore" */ = {

isa = XCConfigurationList;

buildConfigurations = (

999A68431CC86ECD0001FC48 /* Debug */,

999A68441CC86ECD0001FC48 /* Release */,

);

defaultConfigurationIsVisible = 0;

defaultConfigurationName = Release;

};

...Xcode defaults to having a Debug configuration and a Release configuration. While these are pretty common, there is no standard configuration. Do not count on all projects having Debug and Release configs.

Xcode’s project wizard creates a pretty comprehensive Debug and Release configuration for you. And in point of fact, you’ll find out that a lot of these settings can be omitted, because Xcode defaults are pretty reasonable. This is a matter of style. Note that defining everything possible is many hundreds of settings; you might get tired after a bit.

/* Begin XCBuildConfiguration section */

999A68431CC86ECD0001FC48 /* Debug */ = {

isa = XCBuildConfiguration;

buildSettings = {

ALWAYS_SEARCH_USER_PATHS = NO;

CLANG_CXX_LANGUAGE_STANDARD = "gnu++0x";

CLANG_CXX_LIBRARY = "libc++";

CLANG_ENABLE_MODULES = YES;

CLANG_ENABLE_OBJC_ARC = YES;

CLANG_WARN_BOOL_CONVERSION = YES;

CLANG_WARN_CONSTANT_CONVERSION = YES;

CLANG_WARN_DIRECT_OBJC_ISA_USAGE = YES_ERROR;

CLANG_WARN_EMPTY_BODY = YES;

CLANG_WARN_ENUM_CONVERSION = YES;

CLANG_WARN_INT_CONVERSION = YES;

CLANG_WARN_OBJC_ROOT_CLASS = YES_ERROR;

CLANG_WARN_UNREACHABLE_CODE = YES;

CLANG_WARN__DUPLICATE_METHOD_MATCH = YES;

COPY_PHASE_STRIP = NO;

ENABLE_STRICT_OBJC_MSGSEND = YES;

GCC_C_LANGUAGE_STANDARD = gnu99;

GCC_DYNAMIC_NO_PIC = NO;

GCC_OPTIMIZATION_LEVEL = 0;

GCC_PREPROCESSOR_DEFINITIONS = (

"DEBUG=1",

"$(inherited)",

);

GCC_SYMBOLS_PRIVATE_EXTERN = NO;

GCC_WARN_64_TO_32_BIT_CONVERSION = YES;

GCC_WARN_ABOUT_RETURN_TYPE = YES_ERROR;

GCC_WARN_UNDECLARED_SELECTOR = YES;

GCC_WARN_UNINITIALIZED_AUTOS = YES_AGGRESSIVE;

GCC_WARN_UNUSED_FUNCTION = YES;

GCC_WARN_UNUSED_VARIABLE = YES;

MACOSX_DEPLOYMENT_TARGET = 10.9;

MTL_ENABLE_DEBUG_INFO = YES;

ONLY_ACTIVE_ARCH = YES;

SDKROOT = macosx;

};

name = Debug;

};

...By comparison, target configurations are much leaner, and are usually just about settings

related to the target itself. This is the XCConfigurationList for target settings

...

999A68451CC86ECD0001FC48 /* Build configuration list for PBXNativeTarget "xplore" */ = {

isa = XCConfigurationList;

buildConfigurations = (

999A68461CC86ECD0001FC48 /* Debug */,

999A68471CC86ECD0001FC48 /* Release */,

);

defaultConfigurationIsVisible = 0;

};

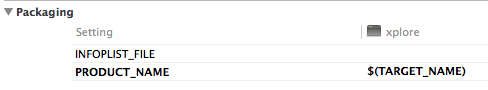

/* End XCConfigurationList section */And here is the Debug target configuration:

999A68461CC86ECD0001FC48 /* Debug */ = {

isa = XCBuildConfiguration;

buildSettings = {

PRODUCT_NAME = "$(TARGET_NAME)";

};

name = Debug;

};The variable $(TARGET_NAME) contains the value from the name key in PBXNativeTarget, and this

in turn is creating an environment variable that is passed to the compiler when it runs. In the GUI

configuration editor for target, it looks like this:

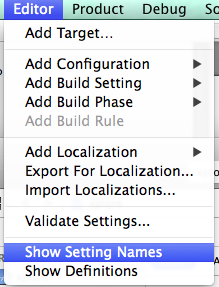

And I have turned on two settings in the GUI, Show Setting Names and Show Definitions, to see the underlying names instead of “human-readable” ones:

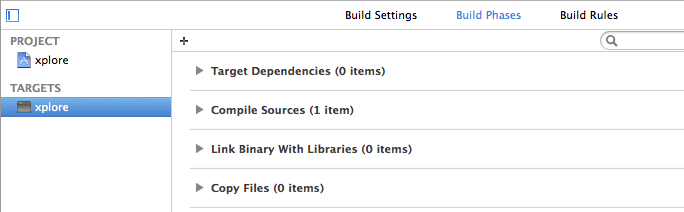

Returning to the PBXNativeTarget object, the most important part from the point of actually

doing stuff is the buildPhases key, which is a list of build phases.

/* Begin PBXNativeTarget section */

999A683D1CC86ECD0001FC48 /* xplore */ = {

...

buildPhases = (

999A683A1CC86ECD0001FC48 /* Sources */,

999A683B1CC86ECD0001FC48 /* Frameworks */,

999A683C1CC86ECD0001FC48 /* CopyFiles */,

);

...

};

/* End PBXNativeTarget section */These are all magic singleton objects. There are a number of possible phases, not all projects have all phases. Here are the possible phases I know about

- PBXAppleScriptBuildPhase

- PBXCopyFilesBuildPhase

- PBXFileReference

- PBXFrameworksBuildPhase

- PBXHeadersBuildPhase

- PBXResourcesBuildPhase

- PBXShellScriptBuildPhase

- PBXSourcesBuildPhase

The two most important ones are PBXSourcesBuildPhase for building your own sources, and then

PBXFrameworksBuildPhase for linking in external libraries and frameworks. In our Xcode wizard

generated project, we also have a PBXCopyFilesBuildPhase, although this is a legacy of how

Unix command-line tools are built (it copies man files into /usr/share/man/man1/, but in vain).

We’ll ignore a Copy Files phase for now.

If you want to see this in the GUI, select a target (in our case, xplore) and click on the Build Phases tab. Since we have no files to copy, Copy Files says “0 items”, and since we have no frameworks or libraries to link against yet, Link Binary With Libraries also says “0 items”.

Since this is a small project, our Sources Build phase is short

/* Begin PBXSourcesBuildPhase section */

999A683A1CC86ECD0001FC48 /* Sources */ = {

isa = PBXSourcesBuildPhase;

buildActionMask = 2147483647;

files = (

999A68421CC86ECD0001FC48 /* main.cpp in Sources */,

);

runOnlyForDeploymentPostprocessing = 0;

};

/* End PBXSourcesBuildPhase section */We have one file to build, indicated with a PBXBuildFile object in the files list in the

PBXSourcesBuildPhase object.

/* Begin PBXBuildFile section */

999A68421CC86ECD0001FC48 /* main.cpp in Sources */ = {isa = PBXBuildFile; fileRef = 999A68411CC86ECD0001FC48 /* main.cpp */; };

/* End PBXBuildFile section */This in turn points to a PBXFileReference object. Xcode’s indirection is a little annoying,

but keeps duplication and duplication-related error to a minimum. In this specific case, I’m not sure

what is gained, because the build file item has no extra annotations on it, but maybe other kinds

of objects have some build-specific annotation that goes here.

The Xcode wizard added a Build Frameworks phase for us as a courtesy, but there’s nothing in it:

/* Begin PBXFrameworksBuildPhase section */

999A683B1CC86ECD0001FC48 /* Frameworks */ = {

isa = PBXFrameworksBuildPhase;

buildActionMask = 2147483647;

files = (

);

runOnlyForDeploymentPostprocessing = 0;

};

/* End PBXFrameworksBuildPhase section */And, that’s the entire wizard-generated project file.

Adding a library to our project

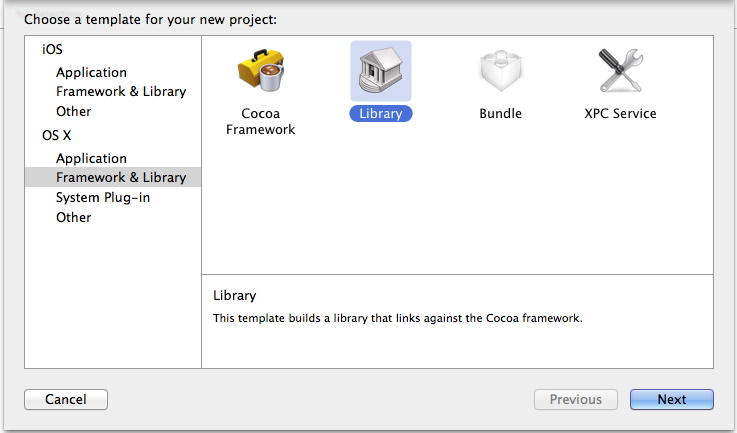

Let’s add a static library to our workspace. This is File -> New -> Project, and choosing static library:

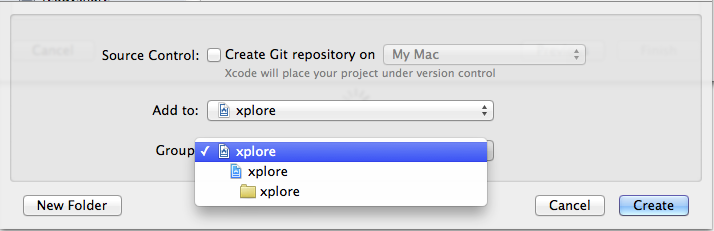

We will name it xlib, add it to our workspace, and put it in the top group.

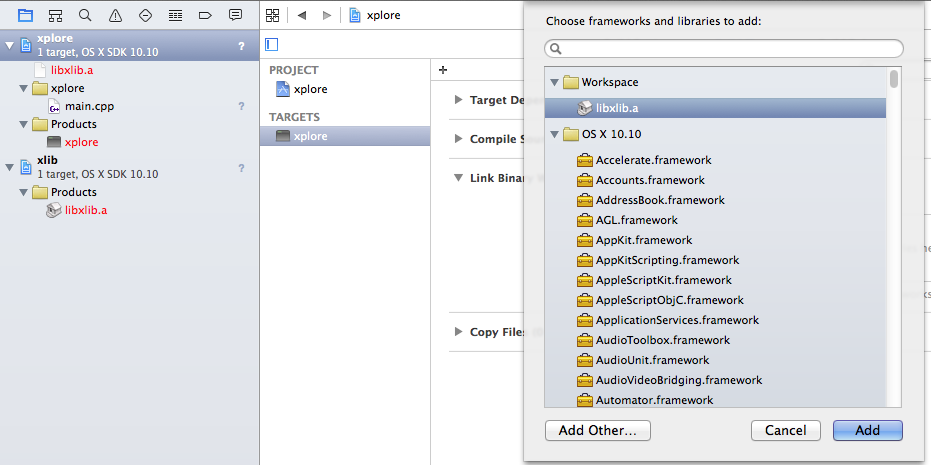

Now, let’s look at the workspace. We see a new project added (it’s in a folder because Xcode likes to do things that way, but we could move it around and edit the workspace to match):

<?xml version="1.0" encoding="UTF-8"?>

<Workspace

version = "1.0">

<FileRef

location = "group:xplore.xcodeproj">

</FileRef>

<FileRef

location = "group:xlib/xlib.xcodeproj">

</FileRef>

</Workspace>At this point, we have a new xlib.xcodeproj that will build a library (assuming we add sources to it), but there are no changes to the xplore.xcodeproj/project.pbxproj file. And if we put code into our static library and built, we would find out that this library is not being linked to from our main command-line binary.

So we add xlib into the Build Frameworks phase:

Now, if we diff the project before and after adding this library to the Build Frameworks phase,

we see a handful of important changes to xplore.xcodeproj/project.pbxproj:

- a new

PBXBuildFileentry to link against libxlib.a - a new

PBXFileReferenceobject pointing to the file libxlib.a - an

filesentry in thePBXFrameworksBuildPhaseobject - a libxlib.a entry added to the top

PBXGroup(which is a weird place to put it) - a library search path added to the

XCBuildConfigurationfor the target